Emil Neufeldt, Chapter 1

In the summer of 1945, in a small town called Neuland, Germany, and elderly 71-year-old man stared helplessly at what had been his home. A couple months earlier, in March, he had left it in a hurry after hearing reports that the Soviet Red Army was soon to invade.

He quickly packed for practicality all of his clothing and whatever food he could gather, while his younger wife greedily grabbed her jewelry. He shoved it all into his Mercedes which he hadn’t been able to drive for years, since 1940. But he’d been saving up his gasoline rations and would use what little amount he had to get south to Czechoslovakia, and hopefully safety.

Now, months later, the elderly man and his middle-aged wife staggered back home. His Mercedes had been confiscated by a fleeing German officer, but still the older man had hope, because he had a large house, with extensive gardens and orchards and chickens—plenty of food to feed his daughters, their husbands, and his grandchildren once they could come back again . . .

Except he didn’t find his home.

He found instead a crater left by a bomb, surrounded by piles of rubble. The crater was filled with water, and floating on the water was his granddaughter’s mattress. Lying on it was a German soldier, dead.

The elderly man stared, realizing that his plans for reuniting his family, currently fleeing west in various directions ahead of the Red Army, were not going to happen. There was no home for them to come home to.

He gazed helplessly at his complete ruin, but not hopelessly.

His looked wearily at the details of the rubble around him, hoping for something salvageable in the remnants of a once-grand house that held hundreds of books and a two-story high music room and beds to spare for visiting grandchildren.

In the rubble he noticed bricks, still intact, and he knew what he had to do.

While his wife stared in despair, then in confusion, Emil Neufeldt stooped and picked up one brick, then another. He carefully brushed them off and stacked them neatly in a pile to the side of the rubble. Then another, and another.

He had to rebuild for his family. There were no other options.

This is the story of Emil August Neufeldt, and of his granddaughter, Yvonne Neufeldt. (Written by his great-granddaughter, Trish Strebel Mercer.)

Emil’s early years

An article written just four short years later in 1949 about Emil Neufeldt, age 75, would have made him rather uncomfortable. The writer, Paul Thomas, a colleague in Neisse who admired him greatly, got a few things right about Emil: he was a very successful engineer for the sugar industry and in charge of the construction of the machinery at Weigelwerk AG, a factory which distributed his machines to more than 50 sugar plants throughout the region. He frequently traveled throughout Germany and Poland to oversee installation of that machinery and, in the words of Herr Thomas, was “honored highly by friend and foe alike.” At his funeral “a large crowd of mourners laid him to rest at the Neulander Cemetery.” (Neisser Heimatblatt, No. 112, “Industry in Neisse: in Memorial of Engineer Emil Neufeldt”).

However, Herr Thomas got a few details wrong. The facts of Emil’s life were actually more interesting than Herr Thomas or anyone else really new.

And also more tragic.

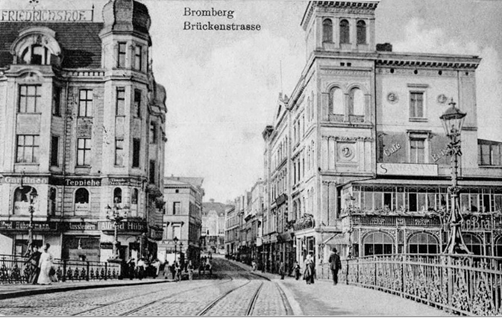

Herr Thomas was correct that Emil was born in Stronau, Kreis Bromberg, on Nov. 27, 1873. At the time it was part of Prussia but now it’s Bydgoszcz, Poland. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kreis_Bromberg.

To say where Bromberg “is” is a rather complicated thing, so to clarify where Emil was “from” takes some explanation. For Americans, the idea that your town many have a different name, language, and even be a different country several times during your life may seem quite strange, but it was reality for Emil. No city in Eastern Germany/Western Poland is easily defined as to where it is because of shifting empires and suddenly new countries.

Bromberg or Bydgoszcz?

To simplify, here’s where Bromberg “was” since the late 18th century:

- In 1772 Bromberg was part of the Kingdom of Prussia (Prussia was its own German-speaking empire for two hundred years, starting in 1701 and ending after WWI in 1918).

So it was Bromberg, Prussia. - But starting in 1803, Napoleon was trying to create his own empire, and he took over Bromberg in 1807, thanks to the Treaty of Tilsit.

So then it was Bromberg, Napoleonic Poland. - But just eight years later, Napoleon was defeated and Europe redrew the boundary lines again. Because of the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Bromberg was once again part of Prussia: Bromberg, Prussia.

- In 1848 Bromberg—still part of Prussia—was assigned to be part of the province of Posen.

- Then in 1871 the German Empire was created, unifying the Kingdom of Prussia with 26 other states to create one country. Emil was born in a country that was only two years older than he was, which means his four older siblings who, while born in the same city as he was, were actually born in a different country.

Bromberg, Prussia was now Bromberg, Germany - In 1918, after WWI, part of Posen began to revolt. In this area were many Poles, and they didn’t appreciate German rule. Battles erupted throughout Posen, but Bromberg never fell. However, the Treaty of Versailles signed in the summer 1919 to punish Germany for its contributions to WWI gave Bromberg, which was filled with mostly Germans, to Poland. By winter of 1920, Poland had full control of Bromberg. Between that summer and winter, most of the Germans left for “safer” areas. By January 1920, Bromberg was Polish.

Bromberg was now Bydgoszcz, Poland. - This new rule lasted only until 1939, when Hitler invaded Poland and retook and renamed Polish cities.

Bydgoszcz was again Bromberg, Germany. - Six years later, in 1945, the Soviet Red Army invaded, the land became Poland again.

Bromberg, German, was now, and still is in 2021, Bydgoszcz, Poland. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kreis_Bromberg.)

In the span of Emil’s life, Bromberg was part of four countries and had six name changes. Depending upon how one refers to the city, you can guess to some of the history they were living at the time.

When Emil was born in Bromberg, Germany, just two years after the Germany Empire was established, the entire region was well-populated with over 700,000 residents (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bromberg_(region)) fairly evenly split between German and Polish descent. Emil grew up bilingual in both German and Polish, which wasn’t as common as one might think, despite the fact that both languages were common in the area.

There remained some occasional animosity between the Germans and the Poles who shared the same land but believed it should belong to their country, and that the “others” living there should leave. However, most people had no problem with the “others.” In fact, Emil’s father was German and his mother was Polish, so there was clearly some crossover and happy marriages between the two nationalities.

Bromberg in an 1890s postcard

Bromberg in an 1890s postcard

Emil’s family

Emil’s father was a forest ranger, and his parents’ greatest hope for him was to also become a forest ranger, or even a farmer, as had been the family tradition. Emil had four older siblings—three brothers and a sister who were 13, 11, 10, and 6 years older than he was. Their occupations are unknown, but it’s possible that they were involved in the family farm or took after their father roaming the forests.

In Bromberg at Emil’s time, there was a society to improve the gardens and town squares. From 1832-1898, the Society for the Beautification of the City of Bromberg and its Environs was active in making gardens and planting trees (https://visitbydgoszcz.pl/en/explore/visitor-itineraries/2907-green.)

But Emil, the youngest son, was interested in something else entirely, and it greatly alarmed his parents. Emil wanted to go into manufacturing and engineering.

Nowadays, in the 2020s, engineering is a great occupation, but not so in the 1890s. Emil’s father, Ludwikg Neufeldt (very German) and his mother Auguste Idzigowska (very Polish) were worried for their youngest child. In the 19th century, manufacturing meant working in factories which were notoriously unsafe, dirty, and noisy. But this was the middle of the Industrial Age, and increasingly it seemed that factory life was the only way to make a living. Such a completely opposite line of work from farming and forestry.

But despite his parents’ pressure to stay out of the factories, Emil just didn’t feel the forests or farms in his blood. He didn’t jump directly into working at a factory, though. During the 1890s he was, at one point, in the army, as the only photo of him in his youth shows. There wasn’t any war at the time, but all young men were expected to provide two years’ of military service for their country.

Emil in the 1890s

Emil and Mariana

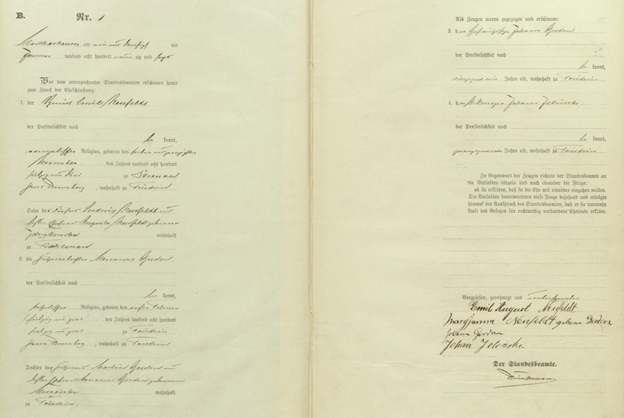

Sometime after this military service he married the love of his life, Marianna Gordon, in 1896. He was 23 years old, and their wedding day, Feb. 1, was also her 24th birthday. She had been born in the area, in Trischin, Posen, when it was part of Prussia.

Mariana was the second oldest of six children, and her parents were Martin Gordon and Marianna Murawka. Her father was a “cottager,” according to their marriage certificate, which likely meant he owned a small piece of property and farmed it. So if Emil didn’t become a farmer, he at least married a woman who had been raised on a farm.

Because of Mariana’s father’s non-Polish-sounding name—Martin Gordon—he may have been of French or British descent. But her mother was solidly Polish.

Mariana was raised speaking Polish first, German second, so she and her new husband were conversant in both languages. Mariana always had a slightly Polish accent to her German.

Emil and Marianna married in Wtleno, now in Poland, which was just a few miles north of Bromberg, and began their family soon after. They happily settled in Bromberg which, in the late 1890s, was still part of the German Empire.

Marriage certificate of Emil and Mariana, in possession of Barbara Goff.

In January of 1898, less than two years after their wedding, their first son was born: Paul Hilarius.

A year and a half later their first daughter arrived, in August of 1899: Helene, who they called Lene (or Lena). Shortly after his second child was born, Emil’s career began to shift.

Emil’s career

In 1900, when Emil was 26, there are records of him working in a factory, just as his parents had feared he would. He was employed in the sugar industry, as the articles written near the end of his life proudly stated.

At the time, sugar beet production was a major agricultural industry in Germany and Poland, and there were dozens of factories in the region squeezing the sucrose out of the beets to dry out and sell as sugar throughout Europe. Imported sugar cane from Hawaii was expensive, so it was a great boon that sugar beets thrived in Prussia/Germany.

“[T]he Prussian chemist Andreas Sigismund Marggraf [in 1747] succeeded in proving that the sugar in sugar cane also occurs in beet[s] – and with this, a fascinating success story began.” (https://www.suedzucker.de/en/company/history/history-of-sugar).

The trick was to get that sucrose in the most efficient way.

Enter Emil. What he was doing between completing high school at age 18 to age 26 is unknown aside from his military service and marriage, but the writers of the articles assumed that he had graduated from college and began his long and illustrious career in the sugar industry right after that.

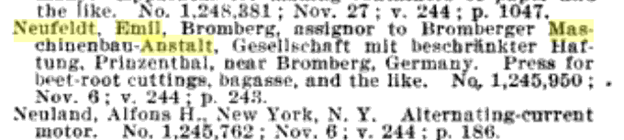

By the end of his life, Emil was known and heralded in several countries as a great inventor and engineer, and over several decades he created and patented many inventions which improved the sugar industry (Thomas). One patent was even recorded in America from when Emil was living in Bromberg.

Official Gazette of the United States Patent Office, Volume 244

However, there’s a problem with this glowing report of Emil’s rise in the sugar factory: he never attended college. That the articles written later in his life proclaimed that he was a college graduate was a source of silent embarrassment for him, but he never said anything about those mistakes.

His parents hadn’t wanted him to attend college. Perhaps they couldn’t afford it, or maybe they thought they could pressure him to follow the forest-farming advocations they wanted for him. But for whatever reason, he was simply working in a sugar factor and then became one of its greatest innovators.

So how did he become a great inventor and engineer?

Natural talent.

In 1900, according to one article, he was installing a newly delivered piece of machinery, a schnitzelpresse (it pressed sugar beets, not schnitzel), in a sugar factory in Niezychowo, now in Poland. But the machinery didn’t work. Engineers tinkered with it, tried it again and again, and still it failed to perform as it should (Neisser Zeitung).

Emil, the installer, was watching and analyzing their lack of progress. Then, when they couldn’t figure out what more to do, he made some recommendations. And with those modifications, the schnitzelpresse finally worked. That’s what started his career as an engineer and designer in the sugar industry (Neisser Zeitung).

Soon he was hired on as a schnitzelpresse engineer and was hugely successful, with only his on-the-job training to guide him. Clearly he had a gift and knew he wasn’t destined for the forests or farms.

His first patent for machinery came about a dozen years later, in 1912, and he kept inventing and earning patents and revolutionizing the sugar industry in Germany and Poland until he was 67 years old, in 1941. Even then, he didn’t stop working for the industry.

And all without a college education. He was a completely self-made man, keenly observant and a natural trouble-shooter. What he lacked in education he more than made up for in resourcefulness and sheer hard work. During his career of over 40 years, he was sent to 54 sugar factories in the region to install his inventions, see what could be improved, then design yet something else to increase the efficiency of the sugar industry.

Emil and Mariana’s family

But back to his growing family. In December of 1902, his second daughter arrived, Hedwig Klara, who they called Hedel.

Another two years after that, Paul finally got a little brother—Roman—who died when he was only a toddler, in 1906.

Another son also followed, but died either at or shortly after birth, and was never named.

In light of the tragic loss of two of their three sons, Emil and Marianna were grateful for the three of their five children who did survive, and lavished love and attention on them. They raised their family in Bromberg, Emil beginning his career as an engineer when he was a father of two young children.

Paul Hilarius Neufeldt

The oldest, their son Paul, was a talented and mischievous boy. He had a great propensity for getting dirty, to the point that when the young family took their Sunday strolls, they learned to set little Paul by the front door in his underwear and dress him only at the very last minute before leaving the house. Even then, he still found ways to get completely filthy which, because Marianna believed in keeping a clean house, was a frustration for her. As he grew older, he continued to not care too much about the state of his bedroom, or his school books, or any of his possessions. Messes were everywhere around Paul.

However, he was a gifted musician, and learned to play the violin well enough to perform solos in their local cathedrals. He was also skilled in math and science. He was bright, very sensitive, and well-liked, with friends everywhere he went. Emil and Marianna had great hopes for their son.

The Great War

Then came World War I, where Paul served for a time in Russia. While he came home safely, the fallout from that war was going to affect the Neufeldts for many years to come.

The First World War was also ironically known at the time as “the war to end all wars” and “The Great War” because it was pretty big and all encompassing, until an even larger war seemingly dwarfed it in importance. Still, up to a staggering 20 million soldiers were killed during those four years of war, and another 21 million more were wounded (https://online.norwich.edu/academic-programs/resources/six-causes-of-world-war-i).

To put it simplistically, the war was officially started when a 19-year-old shot the next-in-line of another country. The action was just an excuse for many of Europe’s countries to finally fight it out. They had been in competition with each other for some time, trying to outdo each other with armies, armaments, and established colonies, all in pursuit of showing which country was supreme in the region. In other words, they were group of schoolboys who had been talking trash for quite a while and were circling each other in the playground, waiting for someone to throw the first punch and finally get it all going.

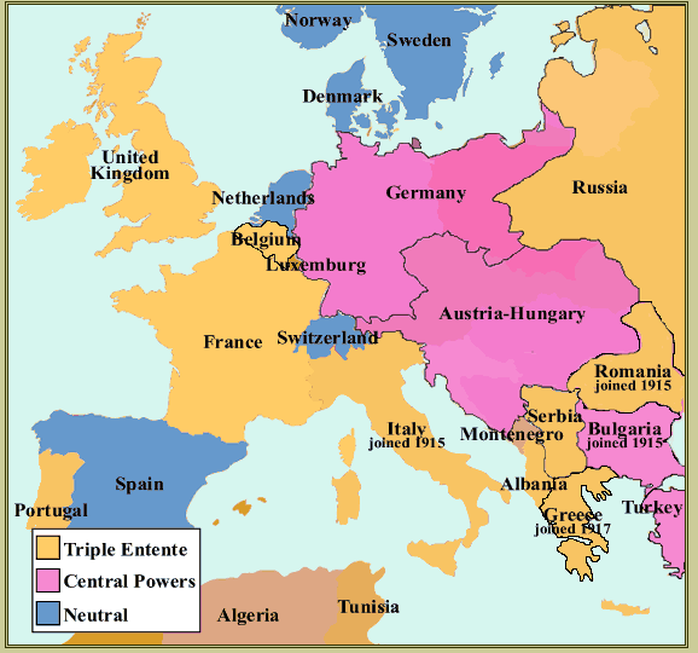

Which empire was going to be THE empire? There were several by 1914.

“No, We’re the best country!”

Germany, for example, had become the German Empire in 1871 by unifying its 27 smaller kingdoms. But it wasn’t the only country trying to expand.

During that time England was growing its British Empire all over the world, and France had been toying with increasing its empire as well since Napoleon had started them on that track. Britain and France were snatching up and ruling territories in Africa and Asia, and new empires like Germany wanted in on the game as well, taking lands in Africa for themselves. These vast regions had great wealth the European countries wanted to exploit, and as expected, the native countries and the invading imperialists often didn’t get along.

There were always tensions, especially if Germany was trying to grab land that France was after in a remote part of Africa. Bigger was better, and many countries were out to prove they were better (https://online.norwich.edu/academic-programs/resources/six-causes-of-world-war-i; https://www.thoughtco.com/causes-that-led-to-world-war-i-105515).

They were also arming themselves in the years leading up to 1914, trying to show who was the strongest boy on the playground. Great Britain and Germany were out to prove who had the biggest warships and the largest navy, while Russia was trying to outdo Germany’s size of army, and succeeding (https://www.thoughtco.com/causes-that-led-to-world-war-i-105515). This drive for militarism focused European countries on not just showing off their manpower and weaponry, but gave them hope to show its effectiveness as well.

Protect the “little brothers”

Since many countries were expanding their territories and forces, smaller countries realized it would be a good idea to pair up with the stronger countries, in case any fighting broke out. Alliances were created to try to keep balance of powers in Europe and ensure the “little brothers” were protected. It also meant that if someone attacked one country, they attacked the entire alliance. By 1914 there were several countries looking out for each other. Allied were:

- Russia and Serbia

- Germany and Austria-Hungary

- France and Russia

- Britain and France and Belgium

- Japan and Britain (https://www.thoughtco.com/causes-that-led-to-world-war-i-105515)

It’s easy to see how an attack on one country, say Britain, would draw in several other countries to fight you in Britain’s behalf. Suddenly you’re facing also France, Belgium, and Japan.

The empire we remember only because of WWI

The Austro-Hungarian Empire allied with Germany in 1879 and 1882 because they were worried about Russia trying to expand into the Balkan region, and they were also concerned about the French growing too powerful in Europe. Later Italy joined them—what then became known as the Triple Alliance—because they also didn’t like how France was trying to gain more influence (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Austria-Hungary). In the middle of Europe, these allied countries hoped to keep the countries on either side from expanding.

With countries gaining power and territory, there also arose a strong sense of nationalism in Europe—pride in one’s own country, and resentment toward other groups living in your country. This was often the case in Germany, and in places like Bromberg where the Neufeldts lived. Such regions weren’t just German, they were also populated with Poles who resented that a few decades before the place was theirs. Borders were frequently redrawn in Europe, with people discovering that the growing empire of one country now meant they were no longer their nation but subsumed into someone else’s.

Where’s Bosnia?

That’s what happened with the Austrian-Hungarian empire, also trying to establish itself during these years. Starting in 1867, about fifty years earlier, the countries of Austria and Hungary combined to rule together. It was a large area geographically, second only to Russia, and larger than the German empire, although Germany had more citizens. About 20 years later, the Austrian-Hungarian Empire took over Bosnia and Herzegovina, which the Bosnians did not appreciate at all. All throughout Europe were little pockets of angry citizens frustrated that their nation wasn’t a nation at all (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Austria-Hungary; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Serbia).

And Serbia?

Another nationality not happy with the Austrian-Hungarian empire were the Serbians. They had become their own kingdom in 1878, recognized as such by other countries, and soon after found themselves in a war with Bulgaria in 1885 and lost the territory they were hoping to win in that war (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Serbia). At the time, the Austrian-Hungarian Empire had come to defend Serbia against Bulgaria, and Bulgaria quickly retreated, leaving their border lines exactly as they had been before the war (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Serbia).

Serbia continued fighting to increase their kingdom and their influence over the next few decades, but the Austrian-Hungarian Empire was holding part of their lands. A radical group of Serbian officers wanted to unite all Slavs, just as Italy had recently united all Italians into one country. This revolutionary group, calling themselves Black Hand, formed in 1901. By 1914 they had committed a few assassinations and were organized enough with hundreds of members hoping to unify all Serb-inhabited lands, including those held by the Austro-Hungarian Empire. One of the leaders of Black Hand was upset that Archduke Ferdinand, who was expected to be the next ruler of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was trying to pacify Serbians about their condition. Black Hand didn’t want their fellow Serbs pacified, but radicalized. They wanted revolution, not peace. So they plotted to have assassins waiting for the Archduke’s next visit to Sarajevo (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Hand_(Serbia)).

A convenient excuse for a war

On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his Sophie drove through the city in an open car, and the citizens lined the road to watch the grand parade which had very little security.

One assassin hiding in the crowd threw a small bomb which bounced off the convertible roof and exploded against another car with minor damage. Three more assassins in place further down the road tried to take the Archduke out, but another man couldn’t get his small bomb out of concealment in time, police were too close to another assassin, and yet another chickened out and ran off. Only by sheer coincidence because the driver took a wrong turn, the Archduke’s car pulled up right next to the last assassin, Gavrilo Princip, who immediately drew his gun and shot both the Archduke and his wife, who died a few hours later from their injuries ( https://www.thoughtco.com/assassination-of-archduke-franz-ferdinand-p2-1222038).

This event—the tensions between Serbia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire—was considered the catalyst for The Great War.

But interestingly, not immediately.

The assassination no one really cared about, except . . .

In fact, no one really cared too much that the Archduke was dead. In Vienna, Austria, the newspapers didn’t even immediately report it, because their Archduke had been a bit of a problem for the government, and they were quietly relieved he was gone. His uncle and cousin were to have been the next in line, but had died, leaving Franz Ferdinand next to take over the empire.

But no one liked him. He had married “beneath” him and the children he and his wife Sophie had were barred by the empire from becoming the next emperors of Austria-Hungary. With Franz Ferdinand out of the way, the leadership of Austria-Hungary could become something else. The only one sort of upset by the assassination was Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany, who had been trying to gain Franz Ferdinand as an ally. The assassination itself wasn’t a world-changing event. It was hardly even noted (https://www.thoughtco.com/assassination-of-archduke-franz-ferdinand-p2-1222038).

Except that it was incredibly convenient, and an assassination should never not be exploited.

This was the perfect excuse for Austria-Hungary to invade Serbia, since they’d been wanting the land the Serbs held. And because everyone in Europe was allied with everyone else, and had armies and navies and munitions and national pride just waiting for that first punch to be thrown, a European-wide war, which spread later to America and Asia, was the perfect stage for every country to show what it was made of, and ultimately decide who was the greatest power (https://www.thoughtco.com/assassination-of-archduke-franz-ferdinand-p2-1222038).

First Austria-Hungary waited to make sure Germany would support them, because Austria-Hungary didn’t feel ready for an all-out war on their own (https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-i/outbreak-of-world-war-i).

A month after the assassination—and with Kaiser Wilhelm’s “blank check” support—Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. Then Austria-Hungary braced for what they knew would come next: Russia. It took only a week for Russia, then France, Belgium, and Great Britain to declare war against Austria, Hungary, and Germany (https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-i/world-war-i-history).

The Great War was finally on.

In many ways it was a messy, useless war. By the end of the four years, and tens of millions of deaths, the Austro-Hungarian empire was dissolved by its enemies. Soldiers engaged in years’ long battles in deep trenches dug all over France and Belgium, fighting for one piece of land with guns, grenades, and poisonous gas, only to gain a few hundred yards to the next trench (https://www.history.com/news/life-in-the-trenches-of-world-war-i). That was on the Western Front.

Paul the Lieutenant

The Eastern Front was different, and that’s where Paul Neufeldt found himself as a teenager. As with many young men, Paul was sent to war and served as a young lieutenant (likely a 2nd Lieutenant https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_Army_(German_Empire)#Warrant_Officers_and_Officer_Cadets). He would have been 16-20 years old during those years of the war, so he probably served toward the end of the war. Since he was a young officer, probably taken from the university he was attending, he likely served around 1917 when he was 19. He was on the Eastern Front in Russia for a time as a cavalry officer, until Russia left the war in 1917.

It may sound unusual to us in the 21st century, but making a 19-year-old college student a lieutenant in the army was rather commonplace.

He may very well have been part of these troops who, as if fighting an ancient war, rode horses and carry lances, but because of modern warfare also wore gas masks, as if in a modern steampunk story.

(Photos downloaded from https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/german-cavalry-lances-1918/)

While Germany’s cavalry started off small—only one division at the beginning of the war against Russia’s 37 divisions, the cavalry quickly grew to hold back the Russians (https://weaponsandwarfare.com/2020/07/05/wwi-german-cavalry-on-the-eastern-front/). Paul was likely fighting for Germany when the calvary was larger.

At the beginning of The Great War, Russia had 140,000 cavalry troops on the Eastern Front, but many were converted to infantry troops later in the war (https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/cavalry).

The same thing happened with the German cavalry. While they quickly built up to 11 divisions, as the war continued, the amount of available horses declined because war takes its toll on animals, and because of the fighting, farmers weren’t able to breed and raise more horses. Many of the cavalry groups had, out of necessity, become foot soldiers.

By the end of World War I, there were only three cavalry divisions left on the Eastern Front, one which may have been Paul’s. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_cavalry_in_World_War_I).

Gas warfare

The reason for the gas masks is because WWI was the first time gas was created and used as a part of warfare.

Starting in 1915, the German army created chlorine gas which, launched into the trenches, settled down and suffocated the allied soldiers. France and Britain quickly started making their own poisonous gasses, and when the Americans joined the war in 1917 they, too, began making chemical weapons. Mustard gas was the worst and most common, created first by the Germans in 1917 to blister eyes, skin, and lungs, and killed thousands of soldiers (https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/germans-introduce-poison-gas).

But almost as quickly as these gases were created, so were highly effective gas masks. If a soldier got his mask on in time, the gas passed by him with no danger (https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/germans-introduce-poison-gas).

Horses, however, didn’t have too many masks, so wherever gas was used, horses—if present—often didn’t make it. In fact, eight million horses, donkeys, mules, and dogs died in WWI (https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/chemical-warfare-hell-even-horses-needed-gas-masks-during-world-war-i-50232).

Eventually some gas masks were created and used for the pack animals and even pigeons who carried messages, as much as possible (https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/chemical-warfare-hell-even-horses-needed-gas-masks-during-world-war-i-50232).

Little wonder that the cavalry began to diminish and soldiers had to continue on by foot.

End of war for Paul

When Paul returned from the Eastern Front, probably in 1917 at age 19, his feet and legs were in a very bad condition. Emil had to help him pull off his boots, which he had worn for at least several days, if not longer, to reveal that his feet and legs were severely infected and covered with bites, likely from lice.

Many men on the Eastern Front suffered from typhus carried by lice (https://microbiologysociety.org/publication/past-issues/world-war-i/article/typhus-in-world-war-i.html). Lice, typhus, and all kinds of maladies were among soldiers in WWI. They endured horrendous living conditions with no ability to clean up or change clothes for up to months at a time.

Few men returned home without some kind of infection or infestation. Paul was relatively fortunate he wasn’t worse off when he finally returned home, although he was quite miserable until he eventually healed.

The Great War ended in November of 1918, with Germany losing and the Austro-Hungarian empire collapsing. Life slowly started to get back to normal, but serious problems were in line for Germany, who received the blame for the war even though Austria-Hungary started it. But since the empire was gone, the next country to blame was Germany.

In the schoolyard fight that was World War I, the first to throw the punches, Serbia and Austria-Hungary, had been knocked out and dragged away. The last instigator standing was Germany, and the rest of Europe wasn’t about to let it sulk away without one last major hit.

Paul’s education

Until those punishments came for Germany, Paul was fortunate to be able to continue with his college education after the war, something Emil wished he could have done as a young man.

Because of the pressure Emil’s parents had put on him to be a forester, he was sure to never put any kind of pressure upon his own children as to what they should do with their lives. What they wanted to become, they could become.

Even so, Paul followed in his father’s footsteps to continue studying engineering in college, eventually going to graduate school in Mittelwalde/Saxony to complete a higher degree in mechanical engineering.

Leaving Bromberg

The Neufeldts loved Bromberg, but in 1919, after WWI, the situation changed. The Treaty of Versailles was intended to punish Germany for its involvement in the war, and one of the many provisions was that areas of Germany be handed over to Poland. This was the fate of Bromberg, along with many other cities. There had always been tensions between the Germans and the Poles, and The Great War exacerbated all of that.

It seemed that all of Europe was out to punish Germany for its participation, and the Poles living in that area of Germany saw their opportunity.

Near the end of December 1918, there was an uprising of Poles against the Germans in the province of Posen, where Bromberg was. But while the Poles took over some areas, Bromberg remained under German control.

Less than two months later, on Feb. 16, 1919, fighting ended because of an armistice between the two nationalities. Germany was ordered to give over Bromberg to Poland as part of the Treaty of Versailles, even though Bromberg was mostly populated by Germans. This was decreed on June 28, and just five months later, by November 25, 1919, plans were made to move all Germans out of Bromberg into evacuation facilities, which would certainly not be 5-star hotels.

By January 10 of that winter in 1920, all state buildings were cleared out of Germans and handed over to Poland. They had less than a month to complete all handover of lands and buildings. On Jan. 19, Bromberg was then officially Bydgoszcz, Poland. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kreis_Bromberg)

As soon as the Treaty of Versailles was signed, Emil and Mariana knew they needed to leave. Even though Mariana was Polish, her husband and children were German, based on their primary language of choice. Conflict was coming, and they knew they should leave Bromberg for somewhere more German.

They left in 1919 ahead of the handover to Poland. One of the articles written about Emil put it this way:

“Because of the deep feeling he had for Germany, he left Bromberg in 1919 [just before the official transition occurred] when it became Polish, and he joined the Weigelwerk in Neisse, Germany” (Thomas).

Again, the author didn’t get it quite right. For Emil’s part, there was no great love for Germany (the author of the article was solidly German and devoted to the Fatherland), just concern about his family’s safety.

A newspaper article written in 1943 did, however get the right spin:

“In 1919 Mr. Neufeldt was forced to leave Bromberg” (Neisse Zeitung).

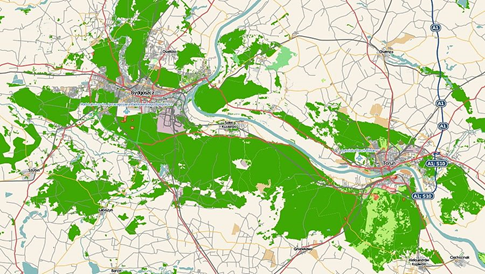

Fortunately Emil had somewhere to take his family. A lot of Germans didn’t. The Neufeldts headed 250 miles south into Germany. Emil and Mariana dearly loved Bromberg and were disappointed to leave it. They headed to Neisse simply because the factory there—the Weigelwerk AG—gave Emil a great job offer he couldn’t refuse.

Bromberg to Nysa, driving distance in 2021

Seeing the political situations changing because of World War I, Emil also realized the move was the best thing for his children who were becoming young adults. In 1919, Paul was 21, Lene was 19, and Hedel was 17, and soon they would be looking for spouses. It’d be safer for them to find German spouses, rather than Polish.

Still, Emil’s heart remained in Bromberg/ Bydgoszcz, and he took his family to visit as often as possible. As a traveling engineer, he stopped there whenever he was in the area, later sending postcards home during his travels.

Germany’s punishment

The Treaty of Versailles brought all kinds of changes to Germany, intending to punish the country for its participation in The Great War. The treaty claimed that Germany started the war (since Serbia and Austria-Hungary were no longer players) and demanded enormous amounts of money to pay off the damage to the rest of Europe because of it (https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-i/treaty-of-versailles-1).

The punishment was staggering:

- surrender 10% of its territories and all overseas lands;

- Germany’s army and navy severely reduced;

- accept full responsibility for the start of the war (since there was no Austro-Hungarian empire to blame); and,

- pay for it all, to the modern equivalency of $33 billion.

No one really expected Germany could pay that, and that was part of the punishment—to keep Germany in poverty and powerless (https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-i/treaty-of-versailles-1).

In these conditions, Emil and Mariana were beginning in a new home, in Neisse Germany. If this was a good move for the family would be up for debate.

Chapter 2, Emil and Yvonne

House on Marienstrasse, Neisse

In these difficult, humiliating circumstances, Germans tried to start their lives again. The Neufeldts were fortunate to purchase a building in Neisse, their new home, on Marienstrasse #4, now Mariacka Street. They bought the building from the Rudolf family, who had two sons slightly older than the Neufeldts’ daughters.

Photo of house the Neisse house on Marienstrasse looked around 1921/22, shortly after the Neufeldts purchased it. (Photo provided by a public librarian, Barbara Tkaczuk, in Nysa, Poland, who happens to currently live in the building next door, 2021.)

Nysa Poland, 2021, with red flag marking the location of the Marienstrasse house.

Niesse house, Marienstrasse, wider view, 2021 Google Maps

As were many of the buildings in the city (in 2019 the population was round 44,000; it was around 35,000 in the 1930s), the Neufeldts’ new home was a multi-story structure. The ground floor was a grocery store, then the upper three floors were partitioned off into large apartments. Emil and Marianna took over the entire second floor, combining two apartments into one. Their second story apartment was a spacious, comfortable place.

Mariacka Street in October 2021, after a recent remodel. Photo taken by Nysa librarian Barbara Tkaczuk, who, amazingly, lives next door. I wrote her asking about the address of Emil and Mariana’s house, and she immediately took pictures because it’s her neighborhood. Note that the arched bridge between the two buildings is the same as in the 1922 photo. Many areas were damaged during the war and rebuilt, but the building on the left—the Neufeldts—was mostly intact after WWII.

Below are additional streets scenes of Nysa in 2021, taken by librarian Barbara Tkuczuk. These are the streets the Neufeldts walked in the 1920s-1940s, views all around their building.

Neisse was a definitely ascetically-pleasing city for the Neufeldts to move to, called the “Silesian Rome” because of its many baroque-style churches and Renaissance buildings. The city was old, founded in the 900s and may have been settled much earlier, since evidence of a Roman settlement was discovered along the river. The city was listed and illustrated in Hartmann Schedl’s 1493 “World Chronicles” as an important Polish city, Nissa.

Although much of it was damaged during WWII, by the 2020s it has been wholly restored.

Screenshot from Youtube: NYSA – dziedzictwo Śląskiego Rzymu, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cFKugK38gcs

Screenshot from Youtube: NYSA – dziedzictwo Śląskiego Rzymu, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cFKugK38gcs

How Neisse looked before WWII. (Who knows–there may be a Neufeldt in this photo.) Screenshot from Youtube: NYSA – dziedzictwo Śląskiego Rzymu, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cFKugK38gcs

How Nysa looks today. Screenshots taken from Youtube video. Screenshot from Youtube: NYSA – dziedzictwo Śląskiego Rzymu, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cFKugK38gcs

The Neufeldts settled in the very heart of this city, convenient to shopping and schools. Combining the two apartments above the grocery store in their building gave the Neufeldts two front entrances across from each other inside, and a back door at the kitchen for deliveries (such as from the grocery store, butcher, etc.). They had three bedrooms, one for Emil and Mariana, one for Lene and Hedel to share, and one for Paul. There was also a gute stube, or sitting room, which was well-furnished.

The walls were faced with walnut, and in the middle of the room was an oval table, surrounded by comfortable upholstered chairs and a couch. One corner was designated for smoking (Emil enjoyed his pipe) with a small table topped with black marble and a few chairs for those who wished to rest while smoking. The room also had a large bookshelf, enclosed with a glass door.

A separate large living room also served as a dining room. The walls in that room were faced in cherrywood, and on one side was a dining table with chairs. By the window was a couch to offer views down to the street below, and a cozy reading corner in the room was furnished with another couch. Lastly, there was another small table and chairs set near the ceramic oven for cold evenings.

All of the rooms were heated with ceramic ovens in those days (and even still now in many European areas), except for the pantry, hallways, and bathroom. While we don’t know exactly what their ovens looked like, there was a wide-range of ovens for rooms, from basic to luxurious. As a major feature of the room, many Europeans wanted theirs to look like a work of art or a statement piece in the room. Some examples can be seen here, and are still used in many modern homes: https://www.rvharvey.com/kachelofen.htm

In Neisse, Emil soon earned a reputation not only as a talented inventor and engineer, but also as a handy man to have around. Everyone in their neighborhood knew if something wasn’t working right, they could call upon Herr Neufeldt and he’d come around and fix it up, for free. He also frequently helped the local Catholic nuns in maintaining their buildings, and became good friends with the Mother Superior, who frequently visited the Neufeldt home in hopes of convincing Emil to become Catholic. But Emil was Protestant, and not really practicing that religion, either. He wasn’t interested in Catholicism or any -ism.

Neisse, around 1920s-30s. The metalwork is a centuries-old cover to protect the town’s Beautiful Well from poisoning.

Inflation and depression in Germany

At the time the Neufeldts moved the Neisse, Germany was beginning to suffer because of the impossible reparations the country was expected to repay. The country made its first huge payment, then had nothing left. By 1922 Germany was effectively bankrupt, but France thought it was withholding payments just to be difficult. So France and Belgium sent in troops to occupy key factories, coal mines, railroads, and steel mills to further cripple Germany’s already weak economy. The German government recommended that the workers in those industries taken over by the French and Belgians just stop working—demonstrate through passive resistance.

No more goods were coming out of those areas, but the workers were still being paid by the Germans. How? Simple: the government just printed more money and handed that out (https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/z9y64j6/revision/5).

But this strategy created a disaster. All of these workers now were flush with cash, but had nothing to purchase. Any goods that were available were in high demand, and people offered more and more dollars (or actually, deutschmarks) to claim those goods. This was the beginning of hyperinflation, and everyone including the Neufeldts felt it (https://mashable.com/feature/german-hyperinflation).

Germany employed 130 printing presses just to keep up with the amount of bills they were producing, and the value of those bills decreased daily.

In 1922 one US dollar was equal to 2,000 marks.

Then it was equal to 20,000, and then a staggering one million marks.

Prices changed daily for common objects, to the point of absurdity. In restaurants, waiters would stand on tables to announce the new, higher prices of meals every half hour. When workers went to collect their pay, they brought long wheelbarrows and suitcases to hold all of the worthless cash they were given. Children played no longer with blocks but with bills, cutting them into paper dolls or turning them into kites or stacking bundles of them like blocks. Women even used the banknotes as fire starters, because the money was cheaper to burn than buying kindling and wood. Even the price of bread was astronomical. In January of 1923 a loaf cost 250 marks. By November it was 200 trillion marks. The bank of Germany was issuing 50 million mark notes just to try to keep up (https://mashable.com/feature/german-hyperinflation).

Emil and Marianna, living in the middle of this mess, recognized that while the rest of Germany was suffering after WWI, they were still doing alright. No matter the country’s situation, people still wanted sugar, even at higher and higher prices. The Neufeldts always had enough food and money, and made it a point to be as quietly generous with their money and goods as much as possible. Taking care of their neighbors and the needy was a priority for them.

Romance in Neisse

Even though Emil preferred Bromberg, Neisse was proving to be a good location for their family, because this is where Emil and Marianna’s daughters finished their education and found their husbands during the turbulent years of the early 1920s. While their oldest son Paul was attending college, his two younger sisters fell in love with the two Rudolf brothers, the sons of the people who previously owned their apartment building.

Helene, called Lene, the older sister, married first shortly after her 22nd birthday. On August 9, 1921, Alfons Rudolf, age 23, became her husband. He was a quiet, serious, and a bit of an introverted young man, but was very kind man and good to his wife. Alfons began his career as a mechanic and, following in the pattern of his father-in-law, eventually became the technical director of a sugar factory in Munsterberg, Germany (now Ziębice, Poland), about 18 miles away and still within easy visiting distance of the Neufeldts.

Top of the page on the left column is Alfons’s name. This is an address/phone book for Munsterberg in 1939.

The same year Lene was preparing to marry Alfons, Hedel encountered his younger brother, Karl, at a Mardi Gras party in 1921. Hedel was 19 and Karl, age 22, asked her to dance. He learned that she was going later to a more formal ball with her parents, so Karl made sure he was in attendance as well so he could introduce himself to Emil and Mariana. He then boldly asked to take Hedel to the theater, and they agreed, but only if Hedel’s big brother Paul accompanied them as chaperone.

Since this was 1921, and inflation was beginning to take off, many people struggled to just find enough food to eat. Karl, needing some help, soon became a houseguest at the Neufeldts’ home—his old house. He wasn’t alone in staying there. Emil and Mariana took in many friends during that time, including Karl and his older brother Alfons, just before his marriage to Lene. Since the Neufeldts had the financial means to obtain food, they made sure they took care of as many people as they could.

Karl was a salesman for Bergmann, a department store, and while Hedel didn’t see him very often, except for occasional luncheon dates, she was falling in love with him. But Emil didn’t approve of him. He noticed how Karl took after his uncle, a Dr. Tannert. While he was a good doctor with a great practice in Neisse, he blew all his money on riotous living. While Karl wasn’t “riotous” like his uncle, he also wasn’t very good at saving his money. He had just enough to no longer need to stay at the Neufeldts. As soon as he moved out, Emil forbade Karl from ever returning to see Hedel.

Hedel was heartbroken, but not ready to give up on Karl. He was pleasant, fun-loving, outgoing and kind. She asked her mother Mariana if she could still see Karl, perhaps when she went hiking with her Catholic youth group in the Silesian mountains, such as at Glatzer Bergland?

Apparently Mariana said yes, because Karl and Hedel were engaged the next year in 1922, but couldn’t afford to marry for another two years.

This delay was quite common at the time, because of the rampant inflation. No one was quite sure what the future held. Plans were made, but put on hold until Germany could settle down again. Germany’s inflation began to stabilize by late 1923 when the government scrapped the old currency and tried a new one, careful not to overprint worthless money (https://mashable.com/feature/german-hyperinflation).

Finally on August 18, 1924 Hedel and Karl could afford to be married, and moved to Breslau, living at Breslau 9 Hedwig Strasse 52, where Karl became a manager of a silk and fabric store. Karl and Hedel loved animals and bought a yearly pass to visit the zoo, then started to have a zoo of their own at their own home.

The main reason Karl wanted a zoo pass was because of a single monkey. When he was 12 years old, his brother-in-law, Paul Gronde, married to Klara, his older sister, visited Cameroon in Africa. It was then a German colony in 1911 (back when Germany was in a race with England and France to acquire African lands). Paul Gronde brought home with him a live monkey and gave it to Karl. Why someone would think a 12-year-old was ready for a live monkey in Germany wasn’t discussed in Hedel’s life story which she wrote, but Karl now owned a monkey, the only one in Neisse.

Karl loved this animal, taking it on excursions to the remains of the wall fortress which circled Neisse. And everywhere that Karl went, he had a following of people. No one had seen someone with a pet monkey before!

But after a few years, the novelty of the monkey began to wear off. Such a wild animal struggled to adjust to the orderly, civilized lifestyle Germans expected. It became a nuisance and caused problems, but Karl still loved it. His family came up with a solution: they donated the monkey to the Breslau Zoo, where Karl could visit it and the monkey could live a lifestyle of a monkey, rather than a German.

Some years later, after the monkey died, it was stuffed and presented to the Steyler Missionary Brothers Monastery for their display of exotic animals and butterfly collection. Karl visited the monastery, even in his later years, taking his children there on the pretext of giving them a good education about animals. But in reality he just wanted to see his African friend, and while his children browsed the exhibit, he would silently and even forlornly stand in front of the stuffed monkey, reminiscing.

Karl and Hedel eventually created their own menagerie of pets, at one point with over 30 birds in cages in their living room, once they moved to Cosel (now Koźle, Poland), about 45 miles away from Neisse. There they owned a successful clothing and fabric store.

Emil and Mariana, with both of daughters in happy marriages, and adding grandchildren, were very pleased.

Now, if only their oldest son could be happy in marriage as well.

Paul and Charlotte

Paul was the last to marry, on August 9, 1926, almost two years after his youngest sister. He was 28, and his wife was Charlotte Weisser, was just a couple weeks shy of her 22nd birthday.

Marriage Certificate of Paul and Charlotte; original in possession of Barbara Goff

Marriage certificate signatures of Paul and Charlotte. Note that Paul’s name is first, then Charlotte’s, followed by Karl Rudolf as a witness, and Charlotte’s brother Werner Weisser.

Charlotte was the daughter of a head waiter, Albert Weisser. Her birth certificate states that her father was Catholic, but her mother, Ida Strauss, was Lutheran. Nothing more in known about her parents or how long they lived, but they were at Neisse Ring #15 when Charlotte was born in 1904.

Paul and Charlotte’s marriage was unfortunately not happy, and very little has been said of it, except for a few facts. For example, on February 20, 1927, Paul and Charlotte became parents to a full-term daughter, six months after their wedding.

It was suggested by some that Charlotte, who was interested in wealth and status (her father being a waiter wouldn’t have had much financially), “trapped” Paul and forced the marriage so she could be part of the now-well-off Neufeldt family. Conditions in Germany were still financially difficult in 1926 and marrying into money would guarantee Charlotte her survival.

She seemed to care very little for her newborn daughter, Yvonne Ida Mariana, and even hired another couple, the Koehlers, to take care of her baby so she didn’t have to. Some may think this depiction sounds unfairly self-serving and even heartless, seeing as how she was only 22 and some years younger than the promising engineer. She couldn’t have been very experienced in motherhood and maybe just didn’t understand what was expected of her. But the harsh depiction feels a little more credible when it’s understood what happened a year later.

Paul, finishing a graduate degree in Mittelsalde/Saxony, was frequently gone that first year of his marriage and his daughter’s life. The distance of over 370 km/230 miles meant he couldn’t return home often. In January of 1928, he became very ill at school. A doctor examined him and recommended that he return to Neisse immediately.

His roommates helped him to the train station, and because the train was packed, he had to stand on the open platform for the long ride home. Of course, trying to stand in the windy outside in the dead of winter for hours on end only exacerbated his condition.

When he arrived in Neisse, he had a high fever to accompany his flu, and headed to his home to rest in the care of his wife and baby daughter. However, when he got home, he surprised his wife in what has only been described as a “very compromising position.” Charlotte wasn’t expecting him to suddenly return from the university, and it’s assumed that Paul had caught his wife with another man.

Distraught and possibly delusional because of his fever and his sheer exhaustion, Paul immediately went out, bought a revolver, and shot himself on January 7, 1928, six days before his 30th birthday.

His daughter Yvonne was not yet a year old and would never have any memories of him except what she heard from his parents, Emil and Marianna.

The loss of Paul

That was a shocking and very dark time for the Neufeldts. Emil and Marianna had now lost their last son, their pride and joy. The entire Neufeldt family was grief-stricken.

To make matters worse, no church would allow Paul to be buried in their grounds, because he was a “murderer.” Eventually one of the churches relented to allow him a Christian burial, but only because he had been an officer during The Great War. They could make a special allowance for his past military service.

Heartbroken and devastated, Emil couldn’t bring himself to attend his only son’s funeral, because he feared seeing Paul’s wife Charlotte there. He couldn’t imagine facing her, the cause of his son’s death. Charlotte seemed to show no remorse for Paul’s passing, and still didn’t care about her baby girl who was now fatherless.

Emil and Marianna and their family were never quite the same after Paul’s suicide. It tainted every wonderful memory and filled them constantly with thoughts of “What might have been.” What if he hadn’t been ill and feverish? What pushed him to such a rash decision? Was he even in his right mind that night? Did he even know what he was doing? No one could know, nor did the answers matter.

Paul Neufeldt, promising engineer, only and oldest son, was dead.

However, there was part of him that remained: Paul’s daughter, Yvonne.

Yvonne, about 1 year old.

Yvonne Ida Mariana Neufeldt

This was the daughter her mother Charlotte wanted nothing to do with, especially after her husband’s sudden death.

Emil and Marianna, however, were more than willing to take in Yvonne and raise their granddaughter. But Charlotte wasn’t going to let that happen easily. No details are known, but there was a legal battle over Yvonne for four long years. During that time, she lived with Friedrich and Frieda Koehler, who were childless themselves but had been caring for Yvonne as an infant when her mother would not. They loved Yvonne immensely and did what they could to help the Neufeldts have time with their granddaughter and finally gain legal custody of her.

Eventually the adoption was approved for Emil and Marianna to have Yvonne, primarily because Charlotte was expecting another baby with a man to whom she was not married. Some speculated that Charlotte kept the legal process going on as long as possible in order to get money from the Neufeldts, but it soon became clear to everyone in Neisse what kind of a young woman she really was and the kind of life she was intent on living.

She had a baby boy in May of 1931 who she named Horst, when Yvonne was four years old and the legal issues about custody were still unresolved. Charlotte, who happened to like and appreciate boy babies, happily kept her new son but never married his father. Her seemingly reckless and immoral behavior made the decision for the courts: Yvonne was awarded to the Neufeldts, with full custody.

Charlotte’s life after Yvonne

While Yvonne later believed that Charlotte left soon after for another town, records indicated that she stayed right there in Neisse. Her first son was born when Charlotte lived at Kochstrasse #2, in Neisse. But there’s no record that she ever interacted with or asked anything about her daughter. Charlotte might as well have been a thousand miles away, except that she wasn’t, remaining in their town where Emil and Mariana would occasionally have the misfortune to run into her. But Charlotte didn’t seem to care, and was happy to have a son.

When Horst was just 17 months old, Charlotte gave birth again to another boy who she named Werner, by yet presumably another man whom she also didn’t marry. She was in a new apartment then, on Grabenstrasse #5. Again, she willingly kept her son.

Three years later in 1935 she had her fourth child, by still another man, but this time it was a little girl named Eva Marie. Charlotte was again living at Kochstrasse #2, where she had been with her first son. Charlotte hadn’t seemed to change her mind about female babies, and about a year after her second daughter’s birth, she gave Eva Marie away to the local baker and his wife, Richard and Marie Elsner, who formally adopted her and changed her last name to theirs. Charlotte cared only for sons, and had no qualms in giving away her daughters.

In a way, that was probably for the best for Yvonne (and her half-sister Eva Marie Elsner who grew up in a bakery), because life with Charlotte Weisser would have likely been unstable and difficult. Charlotte remarried in 1936, a few months after giving away her youngest daughter. Her second husband Gerhard Schneider was six years younger than Charlotte and owned a restaurant in Neisse. His residence was listed as Gierdorf Main Street #96. Charlotte was 32 and her new husband 26. For whatever reason, Gerhard adopted her two boys, giving them his last name of Schneider in November of 1936. According to one rumor, Gerhard may have been a Nazi in 1936, but there’s nothing to substantiate that.

Nothing more is known about Charlotte, her life, or even when she died. Nor is anything known about her children. Yvonne never knew anything else about her mother who readily gave her away as if she were an unwanted kitten, and who never bothered to inquire about her oldest daughter, even though she remained in Neisse for at least the first nine years of Yvonne’s life.

Emil and Marianna desperately wanted their Yvonne. Even though they were 59 and 60 years old in 1933 when the adoption was finally formalized, they were thrilled to have their now-five-year-old granddaughter—the last remembrance of their son Paul—living with them safely in Neisse. Some of their immense heartache was dulled by a vibrant little girl who need their love and attention, and she got everything the Neufeldts could give.

Charlotte and Gerhard

Nothing more is known about Yvonne’s mother Charlotte Weisser Neufeldt Schneider. No photos, no records of death, no information about her three other children.

There is, however, a death certificate for her second husband, Gerhard Schneider. Apparently he was working as a private guard shortly after the Second World War ended in June of 1945. He would have been 35 years old, and had been married to Charlotte for nine years. The “Germany, Deaths of German Citizens Abroad, Registers from Berlin Standesamt 1, 1939-1955” records him as dying on June 23, 1945, in Vienne, France.

There’s no explanation of why he was in France—an unusual place for a German right at the end of the war. France wasn’t too kind to or happy about Germans. Most Germans tried to get out of France as quickly as possible after May 1945. There’s also no indication if he died while doing his duty as a private guard, whatever that entailed (might he have been guarding a ranking German?).

Nor is there evidence about where his wife Charlotte was or his two adopted sons. The death certificate says only that the Register office was able to track down that he was indeed married to Charlotte Weisser, and nothing more as to whether she was still alive or not. If she were still alive and married to him, she would have been 41 years old and widowed for a second time. Not an easy situation to be at the end of WWII when you’re a German with two teenage sons, had they all survived.

Such a lack of information was not so unusual considering what was to happen during the World War II years in Europe. Among the catastrophic death toll was also the destruction of many churches, cathedrals, and town centers where documents—and often the only copies of those records—were stored. Either bombed or burned or stolen, millions of records are missing. For example, the documentation of when and where Paul served during WWI was known to be destroyed with thousands of other pages during WWII. Graveyards were destroyed, desecrated, or bombed. And worse, millions of people died without anyone to record what happened to them.

Someday in the future something may surface about Charlotte, or maybe even a descendant will come forward with the rest of her story (she seems to have had a third son, perhaps with Gerhard, who, in 2022 was an elderly man in Germany, but he’s not responding to requests from Barb Goff to learn more about him). Maybe descendants can reveal that Charlotte eventually came to regret giving up her daughters, that she wondered what happened to them, hoped for their safety, and yearned for their forgiveness. Maybe she came to grieve over the loss of her first husband, Paul, and her actions that precipitated it. Perhaps she felt regret for her early life—nothing is known about her childhood or teen years. It could be that the young woman whom the Neufeldt family came to resent so deeply for causing so much pain turned things around as she matured and aged.

Or perhaps she was lost just a few short years after her second marriage in WWII, meeting the same tragic end as millions of others.

1932 and changes in Germany

But in 1932, when Yvonne was awarded to her grandparents, no one suspected anything of their future. In fact, Germany was at the start of a long-awaited resurgence. After suffering for a decade, it was ready for something better.

The crash and Great Depression in America in 1929 wasn’t isolated only to America—it affected economies worldwide. And because of this great economic crash, many new younger leaders arose in various places promising voters to reform and fix their countries. In Germany, one charismatic, dogmatic, insistent promiser of a new prosperity was Adolf Hitler.

By 1932, when Yvonne was awarded to her grandparents, Hitler had risen through the ranks of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party. With promises to the poor in the lower classes and those without jobs, he believed that “Germany would awaken from its sufferings to reassert its natural greatness.” By end of January 1933, Hindenburg awarded Hitler the position of chancellor over Germany (https://www.britannica.com/biography/Adolf-Hitler/Rise-to-power).

Unemployment in Germany at the time was over six million people (https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/hitler-comes-to-power), and the country was desperate for someone—anyone—to make things different for them. Hitler promised prosperity which Germany hadn’t seen since the end of The Great War and the impossible Treaty of Versailles, which he was now ignoring.

The Neufeldts, however, were still generally comfortable in their circumstances. Despite all of the hardships, the sugar industry had continued, and Emil still needed to visit 50+ sugar factories to inspect and install new machinery which he invented. And now, he had a granddaughter to take around with him.

Yvonne’s new life

Emil and Marianna wanted to make Yvonne’s life as fulfilling as possible, which meant also introducing her to the finer things. Marianna loved the opera, especially the Breslau Opera (now Wroclaw, Poland), and she was a frequent patron. Once, before Yvonne had come to live with them, Emil and Marianna had driven the two hours to Breslau to attend the opera. As Marianna was about to make her grand exit from the car at the entrance of the opera house, she suddenly realized her dress was on inside out.

She panicked for only a moment, quickly getting back into the car and telling Emil to drive around the block one more time. Although the traffic was heavy with those arriving at the opera house, Marianna found a way to remove her dress, turn it right-side out, and redress herself in the front seat of the car before they reached the grand entrance again. She left the car calm, cool, and serene: the very picture of sophistication, in a right-side out dress.

Emil’s Mercedes

A few words about Emil’s car are needed here. He was a lover of the Mercedes Benz, and while we’re not sure of the model, we do know that he favored dark blue vehicles, and the interior of at least one of his cars had a small crystal vase on the passenger side, large enough to hold 2-3 rosebuds. He purchased new models through the 1930s and 40s. During WWII he was one of the few German civilians authorized to purchase a Mercedes, probably because of his past loyalty to the brand. His vehicles were likely the 170 V, and may have looked like this:

The Mercedes website claims that over 91,000 170V were built up to November 1942, the largest amount of pre-war cars built anywhere (https://www.mercedes-benz.com/en/classic/history/mercedes-benz-170-v-the-best-seller/).

This was likely the car that Marianne so deftly changed her clothing in, and when Yvonne was five years old, the kind of car she rode in for her first opera with her grandparents.

Yvonne’s first opera

Yvonne had no memories from her time before she was five, only from the time she was with her grandparents the Neufeldts. In fact, one of her earliest, most vivid memories had to do with her grandmother’s beloved operas.

At Christmastime in Germany there were two productions you could always count on: the Nutcracker ballet and the “Hansel and Gretel” opera, by Engelbert Humperdinck. The opera is geared toward children and runs about 1 hour and 45 minutes. This was likely one of the first grand outings Emil and Marianna took their granddaughter to. Marianna dressed up little Yvonne in a brand-new party dress, and together they entered the opera house. Yvonne enjoyed the performance quite well—the music, the acting, the scenery—and Marianna was probably feeling confident that her granddaughter was going to be an opera aficionado as she was.

Yvonne very well might have been, until the performance was about 2/3 completed, and it was time for Hansel and Gretel’s feasting on the cottage to be disrupted by the witch whose house was being eaten. Maybe if the witch had sauntered in calmly to catch Hansel and Gretel, there wouldn’t have been a problem. But that’s not how witches behave.

No, this witch, dressed in black and with a pointed hat, rushed aggressively on to the stage with her broom, and shrieked.

It was too much operatic drama for Yvonne. Terrified, Yvonne screamed back, but so loud that even the orchestra was startled and stopped playing. Then she did the only reasonable thing a 5-year-old could do: she dove under her chair to hide. The theater security guards helped extract the screaming Yvonne from under the seat, then escorted Marianna and Yvonne from the theater. Even though the performance wasn’t yet over, Yvonne was ready to leave immediately, and the rest of the theater was ready to see them go as well.

Outside, Marianna realized that the chairs must have been recently oiled to keep them from squeaking as people sat down on them, and now that oil was all over Yvonne’s new dress. With the dress ruined and her granddaughter traumatized, Marianna decided it would be many more years before she tried taking her to the opera again. (Indeed, Yvonne didn’t attend the opera again until she was 14 years old and watched a performance of “La Boheme.” She never screamed nor hid under a seat.)

Yvonne and Breslau

While visits to the opera were now put on hold, Yvonne still traveled frequently with the Neufeldts to Breslau, where they went once a month or so for Emil to conduct business and for Marianna to conduct shopping. It was a two-hour drive which Emil always tried to make go by faster by pushing his Mercedes to its top speeds. He believed the Autobahn, which was newly developed during the 1930s, was created solely for him and his Mercedes.

It was good thing he never let Marianna drive, because while she was a woman of fashion, grace, and class, she had no sense of direction. On one of these early trips with their granddaughter, Yvonne remembered walking aimlessly through Breslau with Marianna who was notorious for getting confused wherever she went. This meant that when she was supposed to meet Emil somewhere after his work was completed and her shopping was done, she often wasn’t there but was heading in a wrong direction.

Once they were so confused that it was growing dark by the time Emil finally found them. He’d been driving around several blocks for quite some time. Because it was growing late, and the roads in 1932 weren’t yet lit, and car headlamps weren’t the brightest, the Neufeldts elected to stay overnight and go home in the morning. The closest hotel happened to be The Savoy, one of the premier hotels in the world.

Without any luggage or change of clothes, they checked into The Savoy, much to little Yvonne’s delight. Happy about staying overnight, she promptly climbed on to one of the beds and jumped up and down. Perhaps the Savoy wasn’t as fancy as one might think, because the little girl broke the bed, much to the chagrin of her grandparents and the hotel management.

Emil and Marianna weren’t alone in helping to care for 5-year-old Yvonne. Their daughters Lene and Hedel immediately stepped up, inviting Yvonne along on vacations and visiting Neisse so that she could play with her cousins.

Yvonne’s cousins

By 1932, Lene and Alfons, the sugar engineer who lived in Munsterberg, had a 10-year-old son named Romuald, an 8-year-old name Alfons Junior, a son Norbert who was 3, and a daughter named Christa, who was born two years later when Yvonne was 7.

In the same year, Hedel and Karl, the store owner who lived in Cosel, also had a growing family with cousins for Yvonne to act as pseudo-siblings. Heinz-Dieter was 7-years-old, Olaf was the same age as Yvonne at 5, Peter was 2, and a year later Susie was born, followed by Ingrid in five years later in 1937.

With nine cousins, Yvonne often felt she was growing up in a large family during the 1930s rather than as a lonely child with her grandparents. Vacations and family get-togethers were frequent, and while Yvonne may have lost one mother, she gained three more in the form of her grandmother and two aunts who loved her as they had loved her father.

In many ways Yvonne had an idyllic childhood. She and her cousins entertained themselves with games, with hikes in the nearby fields and in mountains during vacation, and with riding bikes and playing sports in the summer. In the winter they skated, went sledding, and cross-country skiing. Her aunts and uncles taught her and their children all about nature, to peer under rocks and see who was living there, then carefully replace the rocks so as to not disturb the creatures. They helped her develop a love of wild places and animals, and every household had pets. The Rudolfs who lived in Cosel, for example, not only had 30 birds in their living room (and when the exotic blue/black and orange Schamadrossel—a kind of thrush—from Hawaii sang, everyone was immediately sushed to listen to it https://www.zoobasel.ch/en/tiere/tierlexikon/tierbeschreibung/332/schamadrossel/), they also had dogs, fish, and even pet squirrels.

The Rudolfs in Munsterberg also had a menagerie: besides birds and fish, they also possessed a large tortoise. In their backyard was a large fountain set into the ground, and in the autumn Lene and Alfons shut off the water and allowed the basin to fill with leaves. That’s where their tortoise would hibernate for the winter. Everyone watched eagerly for it (they never were sure of its gender) to see when it emerged in spring, because then they knew winter was definitely over.

Because of all the birds the families owned, no one ever had a cat as a pet.

Yvonne’s childhood was as idyllic as her grandparents and aunts could make it. Their homes were always neat and clean and inviting, with Mariana insisting on a beautiful, well-set table with tablecloths and good china, even if it were for just her husband and granddaughter. Well-cooked meals were plentiful, and good manners were always expected. While the Neufeldts and Rudolfs had money, they didn’t throw it around. They believed in purchasing good-quality items, then saving their surplus for rainy days. Money matters were discussed privately, and help was always given to family, friends, and neighbors, as generously as they could afford to be. Emil and Mariana taught Yvonne to never let the receivers of their generosity know if the giving of help required a sacrifice, and often the Neufeldts helped others anonymously.

Yvonne and Mariana

Life at home with her grandparents was peaceful and happy. Mariana loved to do needlework every evening, and often played pinochle with Emil as she did so. But the same distractedness that caused Mariana to frequently get lost in Breslau while shopping with her granddaughter showed up on those evenings. Mariana would try to play cards at the same time she did her needlework, which meant she’d end up losing because she lost track of what was happening during their pinochle game. Upset at losing yet again, she’d loudly accuse Emil of cheating and declared she would never play pinochle with him again! Then, a few minutes later, she’d deal the cards once more stating that she’d try again, but only of Emil didn’t cheat this round, which he calmly stated he never did. Yvonne would just smile at her grandfather, both of them knowing Mariana was a little too frazzled to do both things at once.

Mariana created many beautiful things through her embroidery, knitting, and crocheting. All of the curtains in their home were handmade by her in filet, a type of crocheting, and she also made beautiful sweaters for Yvonne.

However, Yvonne couldn’t stand the woolen stockings Mariana knitted for her entire family to keep them warm in the winter months. They were too itchy for Yvonne, who devised a strategy to keep her grandmother happy, as well as give her own legs relief.

Before putting on the stockings, Yvonne would slip on knee-length socks, then the stockings over them. Out of the house she’d walk, Mariana seeing that Yvonne was wearing the stockings which would keep her legs warm under the uniform skirt which she wore to school. But as soon as she could after leaving the house, Yvonne would duck out of sight, take off the hated, itchy stockings, and shove them in her backpack. For the rest of the day her legs were slightly colder but much more comfortable. Before she got home again, she’d slip the stockings back on to maintain appearances that she had worn them all day long. Mariana never caught on, or if she did, she never said anything to Yvonne.

Yvonne loved her grandmother, who spoke German with a slight Polish accent which Yvonne occasionally teased her about. Emil also knew Polish, so when they had something to say not intended for Yvonne to understand, her grandparents shifted into Polish to discuss. Around Christmas and her birthday in February, Polish was spoken much more in their house to keep Yvonne from knowing what gifts or surprises she might be getting.

Christmas

Christmas was pure enchantment at the Neufeldts’ house in the 1930s. The daughters Hedel and Lene would come with their husbands and children, and everyone packed into the house for the holidays. In Germany, Christmas Eve is the big holiday, and it began with a traditional fish dinner followed by the singing of Christmas carols together. Then the children opened their gifts on Christmas Eve, not Christmas morning. Then, exhausted, everyone went to bed, the grandsons on the floor of the sitting room, while the aunts and uncles and granddaughters had the surplus beds in the house.